The iconic vistas of Yellowstone, America’s first national park, have become synonymous with the definition of the national landscape. It’s unthinkable today for developers to pave over the park’s wilderness, but in the 1870s the barely-settled West was anyone’s game.

Intrepid geologist Ferdinand Hayden invited photographer William Henry Jackson to document his 1871 expedition exploring northwestern Wyoming, and their efforts permanently changed the fate of the Yellowstone area.

Over six weeks that July and August, Jackson photographed what would become the park’s best known features — Mammoth Hot Springs, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and Yellowstone Lake — before most other Americans knew they existed. Seven months later, these images of the future landmarks would help convince Congress to create Yellowstone National Park in March 1872.

Bradly Boner, a photographer, set out to revisit the original sites of Jackson’s images in the 21st century. “I was very interested in seeing how this experiment of the national park… had panned out,” said Boner.

While Boner encountered obstacles — washed away locations and crumbled rocks — he was more surprised by what remained unchanged. It was those moments that moved him the most.

“There were points where I would find individual rocks, like a bowling ball-sized rock, that was sitting in the same place,” said Boner. “Those were the times where you almost feel like you’re looking at a museum or you’re staring through a window into the past.”

Boner’s images of these same places are a visual affirmation of the success of Congress’ declaration. Yellowstone can still connect visitors to nature’s vast sweep of time.

Click on the photos to view images full screen

Mirror Lake

The Hayden Geological Survey traveled along a trail between the Yellowstone River and what is now the Lamar River on August 24, 1871.

The same spot along Mirror Lake is now submerged due to higher water levels. Lodgepole pines burned by wildfires scatter the west shore of the lake, making it challenging to now travel across the Mirror Plateau.

Lower Falls

A path and steps now lead hikers towards the bottom of Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon for a view of Lower Falls. Boner photographed the waterfall from a few dozen feet above Jackson’s exact location because the actual position has been washed away and is no longer safely accessible.

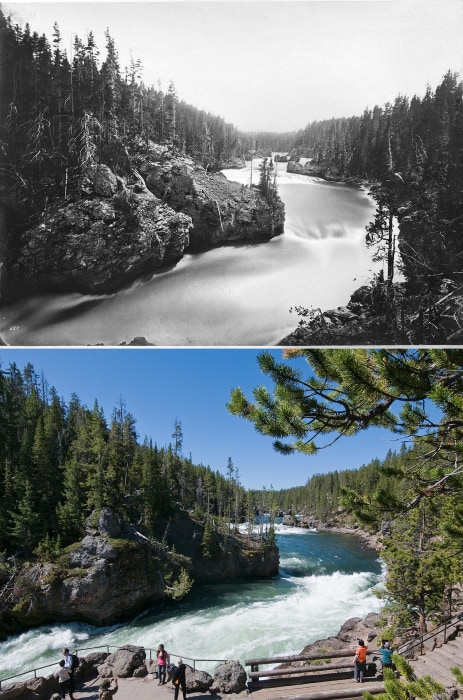

Upper Falls Rapids

The Yellowstone River flows through a series of turbulent rapids just before it cascades to become Upper Falls. Today there is an overlook for visitors at the brink of the waterfall.

Tower Fall

Spring runoffs over the years have moved the rocks and boulders surrounding Tower Creek. According to Boner, the large volcanic breccia visible to the right of the waterfall in Jackson’s image crumbled in the late 1990s, obscured the boulder at the base of the falls and changed the course of the creek.

Tower Creek

Tower creek flows through a gorge surrounded by columns of volcanic breccia rising 50 to 100 feet, before joining the Yellowstone River.

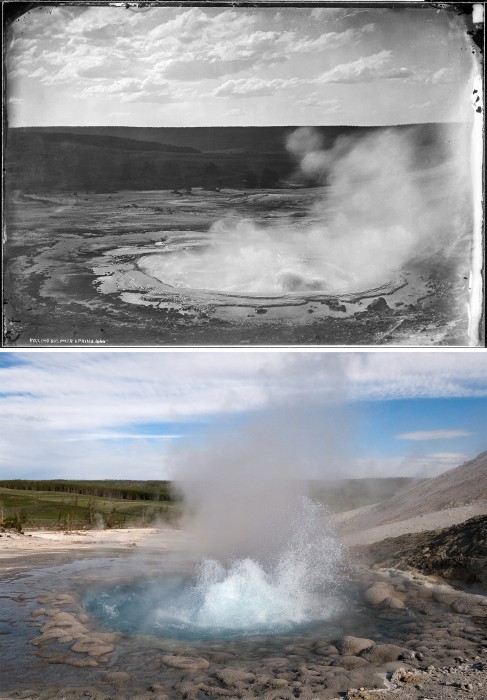

Sulphur Spring

Jackson was taken by the splendor of the sulphur spring in Crater Hills when he photographed it on July 31, 1871. “The water is in a constant state of agitation, and seems to affect the entire mass, carrying it up impulsively to a height of four or five feet,” wrote Jackson. “The decorations about the spring, the most beautiful scalloping around the rim, and the inner and outer surface, covered with a sort of pearl-like bead work, give it great beauty.”

The same sulphur spring is now tucked away in Crater Hills, rarely visited as there is no official trail leading to the site and only the faint markings remain of an old wagon trail. The well preserved geyser continues to be active and will spout water about 15 feet high or more, according to Boner.

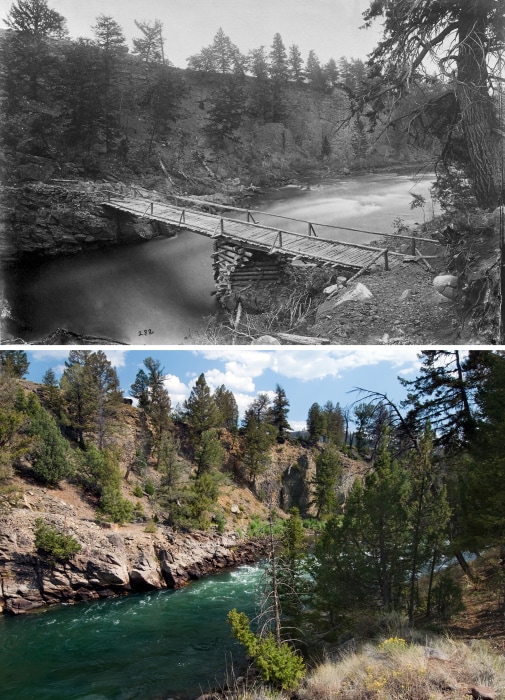

Bridge across the Yellowstone

The first bridge across the Yellowstone River was built early in 1871 for those heading to the Clark’s Fork “diggings,” according to Jackson. The bridge was burned down in 1877 by members of the Nez Perce tribe as they were pursued by U.S. Army soldiers as they resisted relocation to reservation lands. It was repaired the following year and was in operation until 1905. A faint trail still leads to the foot of where the bridge once stood, and a foundation of stacked rocks is still visible on the east side of the river.

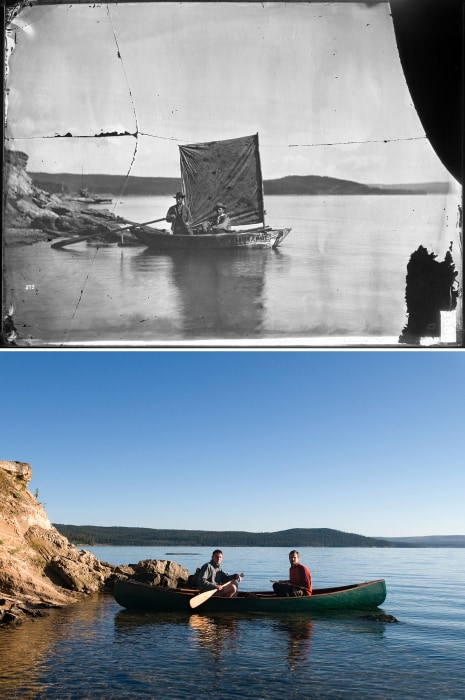

The Annie

Jackson photographed James Stevenson and Chester Dawes, two members of the survey team that set out to cover Yellowstone Lake on August 7, 1871. According to Jackson, the Annie was the first boat launched upon the lake.

To recreate the image along the shore of the West Thumb Geyser Basin, Boner and Matthew J. Reilly, PhD, sat in the canoe they used during the summer of 2012 to locate some of Jackson’s original photo spots.

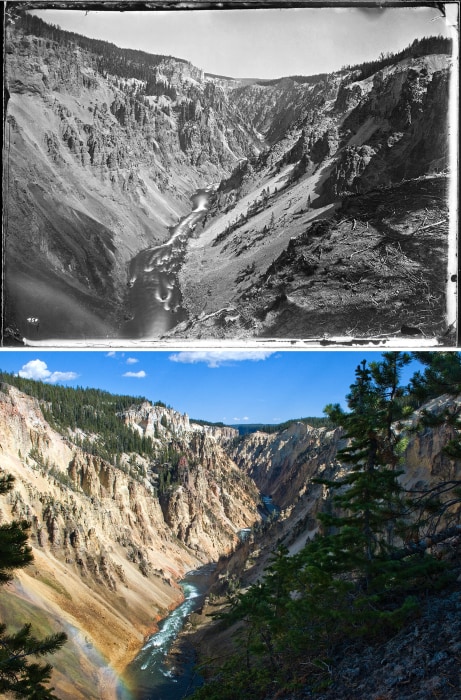

Grand Canyon

Jackson originally photographed the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone in July 1871. The Grand Canyon was the area in the park where Jackson spent the most time, working together with painter Thomas Moran. Boner found his location off the trail in an area not accessible to the general public.

Earthquake Camp

Jackson photographed Earthquake Camp days after its naming when some small tremors shook the area where members of the Hayden Survey were staying on August 19, 1871. East Entrance road now crosses the same location on the east side of Yellowstone Lake. The road is one of five entry points into the park.

Castle Geyser Crater

Vandalism has always threatened Yellowstone, even as early as the park’s establishment. While from this angle, the geyser shows little change, along the other sides, rock formations have been picked off.

“From every part of the ‘Castle’ pieces had been chopped, loosening great quantities of the rock and threatening to ruin the construction,” observed U.S. Army Captain William Ludlow after a reconnaissance of the park in 1875. “Should this continue for another year or two, the beauty of form and outline of the geyser-craters would be destroyed. It should be remembered that these craters were constructed with the greatest slowness by almost imperceptible additions, which can only be made by a discharge from the geyser.”

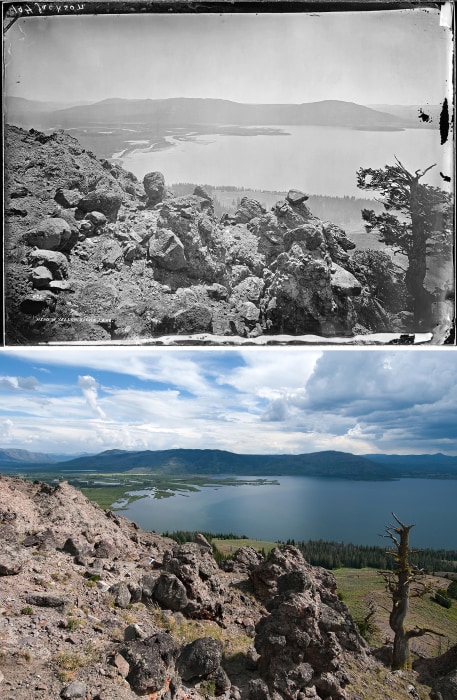

Yellowstone Lake

Rock formations remain little changed after almost a century and a half and a large tree still stands along the southern view of Yellowstone Lake.

Soda Butte Creek

The road alongside Soda Butte Creek has become an active thoroughfare, as one of the few open roads during the winter. A historic tour bus driving on Northeast Entrance road now replaces the horses in Jackson’s image.

Main Terrace

Jackson photographed artist Thomas Moran on the edge of Main Terrace in July 1871. As part of Hayden’s Survey, the two collaborated in capturing Yellowstone, Jackson through his images and Moran through his colorful paintings.

Since then, several hot springs have extended the terraces east, leading Boner to take this photo a few yards away from the original location.

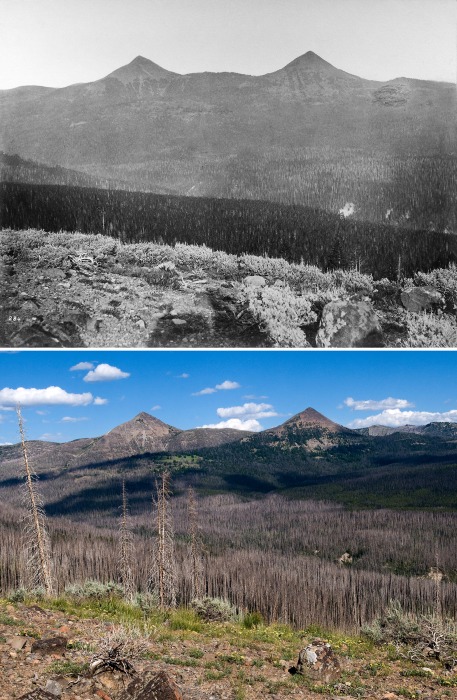

Mounts Doane and Stevenson

With no clear landmarks in the foreground, Boner had to deduce Jackson’s location when he took this image east of Yellowstone Lake. Records indicate that Jackson and survey physician and general assistant Charles Turnbull stood near this spot in the Signal Hills.

William Henry Jackson and Bradly J. Boner’s images of Yellowstone National Park are currently on view at The National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming until August 28.

“Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time” will be published by the University Press of Colorado later this year.